Wintour, Plato & Vreeland: or, how the MET Gala continues to fail the designer-as-artist

The MET Gala has further proved that designers are indeed artists– but that not that many of them are good ones.

In as early a work as the Greater Hippias, one of the dialogues attributed to Plato around 400BC, clothes have been linked with beauty. However, never one to make his points simple, Plato goes on to attribute this beauty to ‘the context of a fraud that is perpetrated on those seeking the beautiful’ (Barnard, 1996). For a long time this definition irritated me: it follows the sexist eighteenth-century notion that clothes are ultimately tools of deceit (Steele, 2001), is almost Kantian in the way it assumes that all anthropological reason can be attributed to the desire to impress ‘superior’ groups (Kant wrote in 1788 that “The saying ‘clothes make the man’ holds to a certain extent even for intelligent people.” but then again, Pearl Jam wrote in 1998 that “I am ahead/I am advanced/I am the first mammal to wear pants”). Most egregiously of all, Plato’s dialogue hinges quite firmly on the general misunderstanding that art (including fashion) is something that is produced for society rather than by it. However, this year's MET Gala has given me serious cause to re-evaluate my scepticism about Plato’s claim.

Truthfully, I am not a fashion writer. I have attended every London Fashion Week since 2018 and have written (rather harshly) about the cultural standing of various fashion institutions (including Vivienne Westwood, which got me in a lot of trouble after I successfully snuck into their show in Paris earlier this year) – but at heart I am an art critic. However, as much as others have been tempted to throw the sartorial baby out with the bathwater, there are too many wonderful and intelligent people working within and writing about fashion for any serious art writer to pretend to be above it. If you are the type of person who requires credentials before a critique, now is your time to decide if mine satisfy. For those of you who are more open to reading about fashion from a contemporary art angle, pull up a chair, order an overpriced coffee, and feel free to light a cigarette. It’s time to get bitchy. (Hey, give me back my lighter.)

There have been plenty of back-and-forths over the years concerning the question of whether or not fashion is art. I shan’t bore you with more Plato, and I certainly shan’t burden you with more modern conservative art philosophers like Roger Scruton or George Dickie, who argue that fashion is primarily concerned with trends and consumerism rather than the pursuit of aesthetic or moral ideals and therefore cannot be characterised as fine art (they’re not wrong, of course, but if we start to discount art that owes its creation to consumerism then we will all very rapidly be out of a job). I will concern myself primarily with liberal contemporary art thinkers, partly because they are those that influence the MET’s and its satelite institutions organisers most directly, and partly because they are far more fun to dissect.

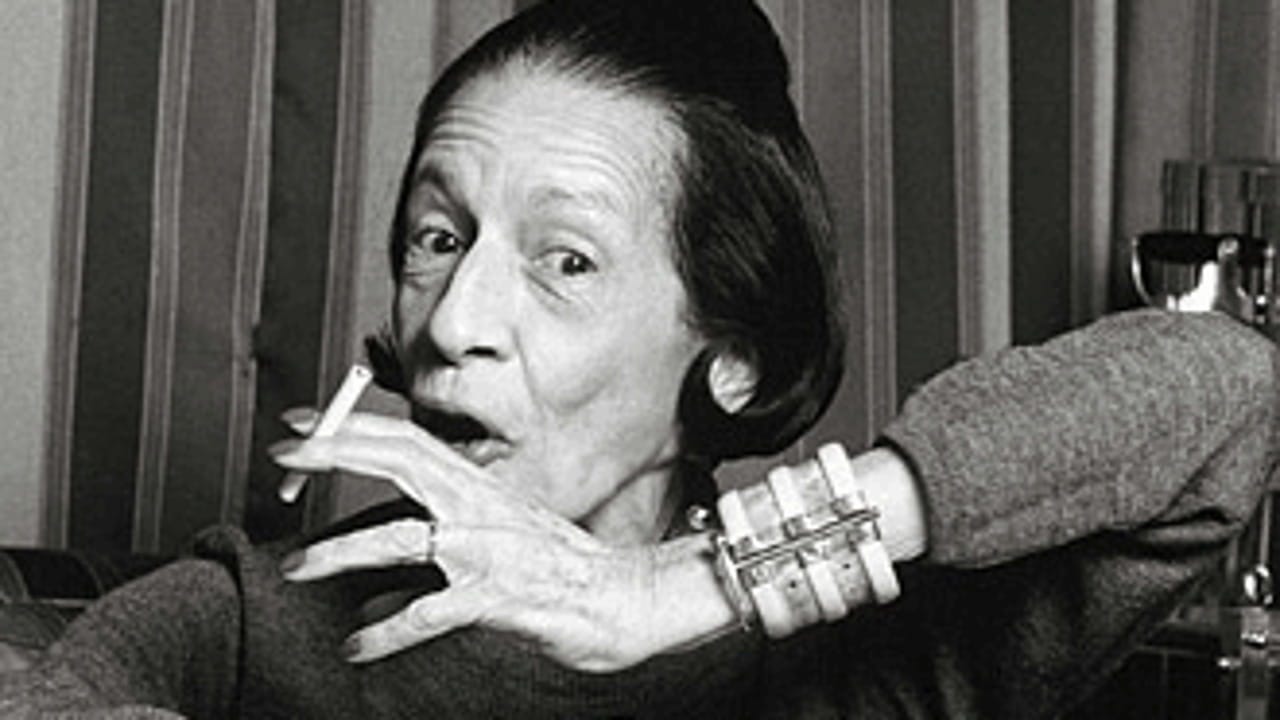

The question of art-as-fashion within popular modern rhetoric most explicitly began to appear during the 1980s, especially in visual arts magazines and fashion exhibitions held in Western and Asian museums and art centres (Kim, 2015). In 1981, the art critic Lori Simmons Zelenko conducted an interview with Diana Vreeland, past editor of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue and former special consultant to the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum in New York. She quite firmly insisted that “fashion is not art”: “Art has to do with something totally spirituelle.” she notes. “It is a very remarkable, extraordinary thing. That is what art is and fashion isn’t. Fashion has to do with daily life… Fashion has a physical vitality, while the vitality of art is not so tangible.” Vreeland also defines fashion as “the whim of the public” and as “ornamentation for the human body,” which “involves craftsmanship”; she holds the view that “art often inspires fashion, when designers search for the creative impulse.” She predicts that “luxury will return” and explains luxury as “a form of thinking, a form of education towards a goal . . . [To] achieve it, knowledge of all the ingredients of the social world, of the different periods of art and literature is necessary.”

I enjoy Vreeland’s analysis immensely, especially considering other fin-de-vingtième art writing concerning contemporary art and its role as commodity (see Robert Hughes, Julian Stallabrass and, of course, John Berger, who all produced fantastically bitchy works about the likes of Warhol and Koons). I especially enjoy that, unlike Scruton or Dickie, she thinks that fashion shouldn’t be considered art because, unlike art, it’s actually important. However, to say I enjoyed her words does not mean I agree with them and until recently I thought she was mostly wrong, especially concerning her definition of “vitality”: in particular that “the whim of the public” discounts any artisanal practice as being considered art, and that luxury and the knowledge required to admire it is separate from populist goals of command and cognition. However, looking at the intersection of contemporary art and the pieces produced for this year's MET Gala, I believe she may be entirely correct.

In her interview with the Met in 1967, sculptor Louise Nevelson noted that “I was reading about an art opening and every woman, even the ones who had collected all those beautiful things, was identified by who designed her dress, not by how she looked or what she did. It's insanity to negate these ladies, reduce them to a label.” Sparked by Saisselin’s consideration of the fashion–art relationship, both Vreeland and Nevelson (unlike Plato and, to a lesser extent, the current organiser of the MET Gala Anna Wintour, but more on her later) correctly assume that fashion is a reflection rather than a reaction of those who wear it. Man is a self-staging and self-reflecting being that seeks recognition. Fashion is anthropologically remarkable simply because there is no escaping it: we all wear clothes, and even those of us that forgo the traditional Western-capitalist approach to the sartorial prison are making a statement of some sort (see the rise of tradwife and homestead content).

In this way, fashion is possibly the most political of all art. Cultural figureheads from Paula Scher to Frank Gehry have tried to argue that this is true of their own practices, but realistically one can go one’s entire life without thinking about the kerning on the poster outside their apartment or the angles of the living rooms inside their homes. We can not and do not go through life without thinking about the clothes we put on our bodies. Events like the MET Gala, then, help us in understanding how we, in an increasingly class-conscious yet class-confused society, consolidate this obvious and everyday “vitality” as Vreeland puts it with events by (but not necessarily for) the super-rich.

If I am to agree with Scruton and Dickie on one thing, it is that it is true that the question “Is fashion art?” has generally been answered by those who stand to make money off of the answer being “yes”. Disagreement concerning what does and doesn’t count as art among philosophers of art is mirrored by disagreements among practitioners within the fields of the arts (Monsiere, 2015). However, Richard Kamber is incorrect in arguing that philosophers cannot simply presuppose the universality of their own intuitions and use these intuitions as evidence for their theories of art. Polaire Weissman, Executive Director of The Costume Institute, defines fashion as “a point of emphasis that shifts from one area of the body to another, changing the external aspect of the human form, and how these shifting accents recur. It should be evident also that fashion is an inherent part of art in environment, and that the phenomena of fashion could not survive without the creativity of those who give it substance.” (Weissman, 1967).

I love this definition, and Weissman’s own investment in it being correct does not mean the view of fashion-as-art should be disregarded. It is still an entirely noble and philosophically sound mode of thinking.

As noted I have no skin in the game, but I will defend the role of the designer-as-artist. However, it’s still worth considering what does count as fashion-as-art if only to understand what delineates an artisan from an artist. Malcolm Bernard does an excellent job of attempting to answer this question in his 1996 Fashion as Communication, as does Lars Svendsen in his 2004 Fashion: A Philosophy (with differing conclusions) and I highly encourage anybody with a vested interest in forming their own opinion to peruse both.

One of my current favourite fashion critics is Nikesh Pandya-Gudka (notsoquietluxury on Instagram). In a video about Lotta Volkova’s styling of Miu Miu’s latest campaign, Pandya-Gudka brings up the notion of storytelling; more specifically Volkova’s ability of being able to “place Demna [Gvasalia]’s vision of socio-political commentary onto the runway” during her time at Balenciaga. McQueen is the obvious example of this; and Pandya-Gudka is entirely correct not only in praising Volkova, but in reminding us that what makes a designer truly extraordinary (and what makes him or her a good artist) is their ability to tell a story. Art should always have a message, and if I am to cautiously suggest a pennant by which to judge a designer’s success as an artist, it’s that it should rely on how concisely and beautifully they communicate this message within the parameters laid out by Weissman.

Now, onto the juicy stuff. The MET Gala’s theme this year was Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion with a dress code of ‘garden of time’, in reference to JG Ballard’s short story of the same name, set in a surreal pastoral landscape where time is represented as a physical entity. I have loved Ballard since being made to study The Enormous Room at uni, and to give credit where it’s due the MET Gala has always chosen really yummy literature to accompany its theme. Wintour is clearly extremely well read, and although I personally find her own style absolutely atrocious she clearly deserves her reputation as a titan when it comes to picking poignant and beautiful essays (yes, yes, what a surprise that a woman in her twenties adores Sontag).

Time and its passage is an immensely important motif in the history of art. In his discussion of a Ben Bertocci painting, Taylor Morrison (another current fave of mine, weopen on Instagram) talks about how in cave paintings ‘piercing’ was used by early shamanic societies to mark an experience within place and time. One of the earliest examples of a calendar is the Ishango bone, considered to be oldest mathematical artifact in existence: a notched mammal bone likely used as a menstrual period tracker. Vanitas still-lifes and momento mori sculptures permeate Medieval and Renaissance art.

Contemporary art has attached just as much importance to representing time and its passage. Felix Gonzalez-Torres' clocks, symbolising the artist's HIV-positive partner Ross Laycock and his decline and inevitable death, is one of the most well-known artworks to come out of the AIDS crisis alongside Keith Haring’s final unfinished work, also an exploration of time-as-ending. Hirsts’ taxidermy suspends time, Kawara’s Today series documents it, Salcedo’s Shibboleth embraces it. Translating these static motifs into something as living as fashion is not an easy task, but it shouldn’t be.

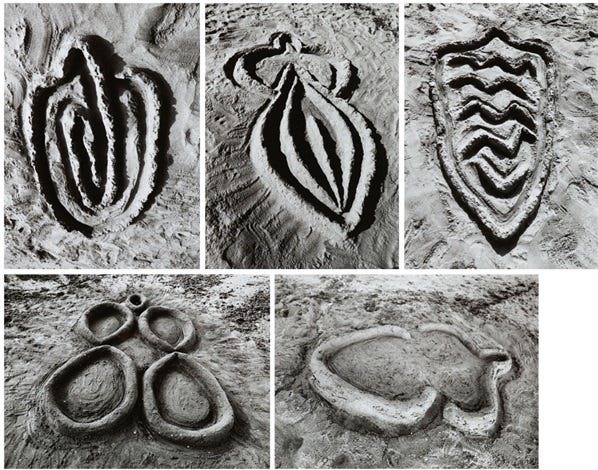

I spoke briefly on Instagram earlier this week about Olivier Rousteing’s Balmain ‘sand dress’, worn by singer Tyla. I will briefly recap the points I made then: considering Weismann’s parameters of fashion-as-art’s role a “point of emphasis that shifts from one area of the body to another” it is an utter failure of an artwork. We’ve all seen the videos of her being lifted from step to step: Tyla’s body is nothing more than a podium for Rousteing’s work. I originally suggested that perhaps the piece would have functioned better as a sculpture but upon seeing some close-ups of the shoddy craftsmanship I rescind that idea (poor Tyla was holding the dress up by the end of the night as the seams beneath the armpit had split under the weight of the train, which was removed by Rousteing in a poor attempt at what can generously be described as process art, but more on that later).

I will note that it was surprising to see how adored this piece was considering the outcry over Kim Kardashian’s weightloss for her Monroe gown (and her simply unbelievable waistline for both this years’ and lasts’ Gala), but that’s a whole other can of gesso. However, in this regard Rousteing and Tisci were not the only designers who failed.

Mobility is a vital aspect of fashion-as-art. I do believe sculpture is one of the highest levels of art and to be able to translate it into something that functions, as Weismann puts it, “an inherent part of art in environment” is not an easy task. Sculptures can take any form; fashion must work within the physical space or environment attributed by its’ wearers body. That so many of these garments failed to function (in the literal sense) within these parameters is massively telling.

There were so, so many dresses that simply could not be moved in. Tyla was manhandled like a doll. Dozens of Gala denizens had trains that were inorganically yet meticulously placed along the steps for seconds at a time. Cardi B (who forgot her designers name) needed nine men to lift her dress, and was originally meant to stand on a podium. Amma Song’s REDDRESS 2004 installation has already explored how fashion and art has and continues to treat women’s bodies as platforms for art, specifically as champions of the female’s place as stage for aesthetic beauty (I attach Aristotle’s frankly hilarious view of women's role in aesthetic and genetic inheritance, physiognomy and telegony below - note the parallels between later Medieval alchemists views of heat and cold/mercury and sulfur/male and female - and, of course, contemporary online discourse concerning the divine feminine/masculine 🙄).

The garments present at this year’s MET are created by and for people whose concept of art was limited to that singular moment on the red carpet, the ephemeral aesthetic to be captured once and potentially forgotten. You can generously attribute this to the proposed environment and say that the artists are simply working within the physical space they were given. But the carpet isn’t the only space in which they exist: there’s the dinner, the dancing, the pretending-to-piss-in-order-to-do-fat-slugs-of-coke (Hailey Bieber darling, we all know what you mean by “smoking”) in the bathroom. Clothes are meant to be worn, for Christs’ sake! The continued insistance that these works should exist only for the minutes in which they are being photographed on the carpeted stairs seems to suggest that if Sinna Nasseri doesn’t take a picture of your stupidly long train that it never even existed.

All art is slowly becoming process art. From ‘get ready with me’ videos to endless reels of artists mixing paint and having breakdowns, we are as a society becoming far more obsessed with the ‘before’ than the ‘after’ of artworks. The MET Gala does its best to remedy this hellish situation by compromising with obsession of the ‘now’ as defined by the axioms of the ‘then’.

It is not a coincidence that the theme of this years’ ball relied on the reanimation of archival pieces, especially when considering how prevalent fast fashion has become. Think of the ‘old money’ trend - originally designed as a way for Eurotrash (affectionate) to fight back against the nouveau riche styles brought into Western metrocapitals by young Arabs and Asians (an ostensibly neanderthalithic, ‘we were here first’ reaction, but I digress), then quickly adopted by Americans whose wealth probably only stretched back a few decades at most, which naturally trickled down to budget brands from Zara to Shein.

Historicity is the only real remaining way of flagging one’s belonging to an industry increasingly defined by fleeting microtrends and temporary cashgrabs: after all, McQueen won’t lend that gown to just anyone. Conflating the rich with the famous might be a mistake when considering general economics (we all know Kylie Jenner is alledgedly broke) but it is an entirely fair coalescence to be made in the world of fashion, especially when considering the MET Gala.

As time marches on and the lines between wealth become increasingly blurred, it is natural that the ruling class (at least in terms of cultural aesthetics) will seek out ways to further distance themselves from the underdogs: note, for examples, how few influencers were at the 2024 Gala compared to a few years ago. To return to our chain-smoking bestie Vreeland’s claim that luxury is “a form of thinking, a form of education towards a goal [that requires] knowledge of all the ingredients of the social world, of the different periods of art and literature is necessary”, I find myself believing that she predicted something really rather major. Contemporary art no longer requires us to know about science; we are too engrossed with breaking the rules to learn them in the first place. The ubiquity of the scientist-as-artist was lost sometime during the early twentieth century and it’s finally caught up with the world of fashion: fashion should be a celebration of engineering, of chemistry, of spacial awareness and choreography. Look at McQueen, at Yamamoto, at Mugler, at Balenciaga, at Schiaparelli: storytellers supreme, masters of technique and message. This is not to say I don’t like titans like Van Herpen, Dior, Chanel, Jacobs — I would kill and die for a pair of Kiki boots — but on the contemporary stage, where is the story? The glory of allegory over the mundanity of image? They are artisans, excellent ones at that, but not artists. The MET Gala has further proved that designers can be artists– but that not many of them can be good ones.

Bibliography/Further Reading

- Armand Marie Leroi - The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science (2014)

- Robert B. Louden, Manfred Kuehn - Kant: Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (2006)

- Malcolm Barnard - Fashion as Communication (1996)

- Oscar Wilde - The Artist as Critic (1891)

- Polaire Weissman - The Art of Fashion in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Nov 1967)

- Sung Bok Kim - Is Fashion Art? (2015)

- Valerie Steele - The Corset: A Cultural History (2001)